By Tony Attwood

Way, way back before the dawn of time, well before the pandemic anyway, I wrote a few articles about the state of the finances of certain clubs, noting in particular how Wolverhampton Wanderers had borrowed a sum equal to their next TV payout, in order (it seemed) to make stage payments for transfers previously concluded.

Way, way back before the dawn of time, well before the pandemic anyway, I wrote a few articles about the state of the finances of certain clubs, noting in particular how Wolverhampton Wanderers had borrowed a sum equal to their next TV payout, in order (it seemed) to make stage payments for transfers previously concluded.

They had also borrowed money to get promotion in 2018, and were working to hold their position in the top flight.

That borrowing was a bit of a warning sign, and unfortunately for them it came just before the pandemic. I imagine further borrowing has taken place to keep them going, again secured by future TV money.

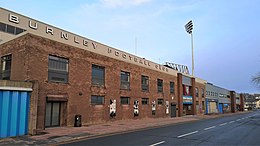

Meanwhile we don’t normally associate Burnley (the home of the rag pudding and attie ash) with large amounts of borrowing. And in fact they haven’t done too much of that – for instead of being owned by Lancashire people (as they have been since the foundation of the club over one and a quarter centuries ago) they have been sold to investors in the USA and the ground has been mortgaged to an American investment company.

In fact there are now investment companies circling around a number of clubs. Sunderland, Derby and Southampton have already fallen are all in hock to the same investment group. And of course most of the time these deals which are often eye-watering are kept very quite.

But recently details of one of the deals did emerge, and it turns out that Southampton are paying 9.14% interest on a loan they took out nine months ago.

Now as we all know, interest rates generally are being quoted at less than 1% so why would any set of directors in their right mind toddle off and sign up to a deal at 9.14%?

Several reasons come to mind…

First, and most obviously, no one else is lending to football clubs.

Second, the lender sees football clubs as vulnerable and so they need to protect their interest.

And third, the feeling of concern, worry and in the end panic that has been floating around the world of football finance since the Sunderland deal was done, has now morphed into a feeling that the end is nigh.

We should note however that the Sunderland loan has now been paid off, and the club sold, but such deals are becoming harder to find – and the deal in itself doesn’t mean the club is safe.

One key point of course is that these loans are secured against the clubs’ assets – that is to say, the ground and the value of the players. Another is that all these deals were done before the pandemic, and all the decline in revenue that has been part of the game since then.

But the Southampton borrowing is particularly interesting because it is seemingly to cover the losses they are making during the pandemic.

As a further sign of difficulty, a number of clubs (including Southampton) now seem to be up for sale. And that means that buyers have a choice of clubs, and a chance to knock down the price.

In the past such crises have been survived by and large because there has been a large number of overseas buyers who want to move into English football. However this market has shrunk. Difficulties with China which have resulted in that country not showing Premier League football on prime channels any more, has removed a number of potential bidders, and the virus and its impact on football has caused a lot of companies to reconsider their investments (which also explains the eye watering interest rates being charged).

It is also notable that the only firms who seem willing to extend credit to football clubs at the moment are those based in the Cayman Islands, meaning the owners are hard to trace and are most certainly not available for interview.

And there is another worry. In France a number of clubs are hanging on but only just (as we might notice Lille has just been sold to a hedge fund). Their problem is not just the pandemic but the fact that the €814m a year TV rights deal (which should have lasted until 2024) has collapsed, after MediaPro went into liquidation.

This happened because the bid for the rights was generally seen to be far too high and only one sixth of the number of subscribers needed actually signed up. The payment for last October to the clubs failed to be delivered, and the top leagues in France are still looking for a new TV company.

What is interesting is that many people in the broadcasting world were uncertain about MediaPro’s ability to make such a deal work, and indeed the Serie A clubs turned down a deal with MediaPro because of a lack of financial guarantees. Italian clubs and financial probity: now there’s a thing!

Of course some clubs will be ok because their owners are backed by a sovereign wealth fund. But there seems to be a lot of clubs whose entire financial projection was based on the notion that “we’ll be all right”.

Maybe so, maybe not.